This week in Newly Reviewed, Max Lakin covers Enzo Shalom’s ghostly naturalism and two group shows drenched in nostalgia.

Tribeca

Enzo Shalom

Through April 19. Bortolami, 39 Walker Street; 212-727-2050, bortolamigallery.com.

The Surrealist Max Ernst considered frottage — the technique of rubbing over a textured material — an “automatic” form of production because you could never anticipate what you would get. The images Ernst got, by rubbing soft pencil on paper draped over wooden floorboards, suggest spectral forests.

Enzo Shalom achieves a similar ghostly naturalism in his enigmatic, process-based paintings. Thin layers of semi-opaque oils obscure and reveal; ugliness knocks into beauty. His cool, loamy palette could easily get muddy, but Shalom is specific in his articulation of color. He uses the same red clay that Degas used, along with zinc white, warmer than the typical titanium shade, which all stays crisply distinct.

Floating above are Shalom’s frottages, subtle forms of tremulous lattices. They are like root systems or excavations of Manhattan schist — apparitions, as Henri Michaux (another frottage specialist) called his rubbings, of a world we can barely see.

There’s a restless experimentation: paint applied to canvas and linen, but also to jute, paper and board. He sands down his substrate or builds it up with collaged pieces or layers of thin rice paper mounted to an aluminum composite and ironed out to a slick sheen.

Shalom is after something, though it’s hard to be sure what. Maybe the not knowing is the point, the figuring out of how to work with or against his materials, the willingness to let them dictate the image. This handle on abstraction’s mutability, the ease with which it slips between moods, is where the paintings really come alive. MAX LAKIN

Upper East Side

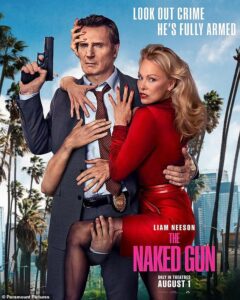

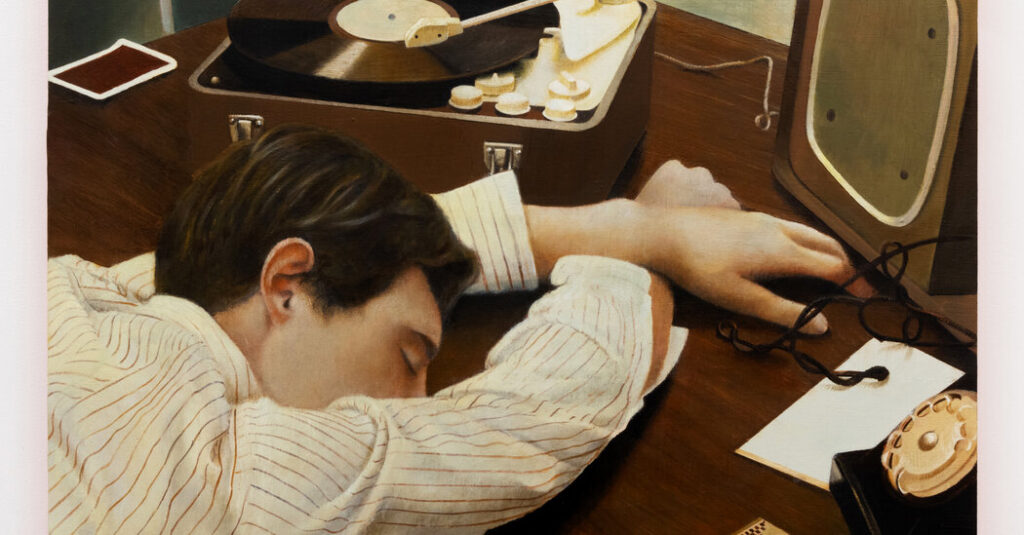

‘Landline’

Through April 25. Turn Gallery, 32 East 68th Street; 917-773-8263, turngallerynyc.com.

Analog signifiers recur throughout analog means in “Landline,” a wistful four-artist show that pines for a pre-iOS way of life where the most sophisticated piece of technology was a well-thumbed copy of TV Guide.

Bernie Kaminski’s papier-mâché sculptures conjure a specific New York experience — Zabar’s, pastrami on rye, Mets fandom — that remains durable, even as many of the hangouts memorialized here via matchbooks (Moondance Diner, Florent) have not. Kaminski’s versions are faithful, though only to a point. His wobbly penmanship and bumpy surfaces happily betray a human hand, transmuting them into totems so potent that you expect a dial tone out of his Bell pay phone.

Karyn Lyons’s brushy, languorous scenes of an affluent, vaguely melancholic adolescence could storyboard a Sofia Coppola film. Her teenagers are lonely even as they appear to occupy a Titian painting, with only the groundskeepers or a stack of magazines for company. Perhaps in that pile there’s a Mademoiselle or Harper’s Bazaar, where Gösta Peterson’s photos of young women mooning into a pay phone box, say, were the picture of modernity when they were published in the 1960s and ’70s.

Kaminski and Lyons were born in 1966. Leonard Baby, born 30 years later, is too young to have a direct memory of the rotary phones he paints with soft, almost unbearable longing. His anemoia — nostalgia for a time one has never known — can feel cloying, but it would be dishonest to deny him his ennui, his suspicion that progress has left something important behind.

Sometimes nostalgia is correct. The smartphone reflex is by now muscle memory. Fainter, but still there, is another, when phones needed to be tethered to the wall and connecting was an act of willful determination, not a cynical compulsion. MAX LAKIN

East Village

‘Before the Clean-Up’

Through April 5. Smilers, 431 East Sixth Street; 646-389-0084, smilers.nyc.

You can’t really make out much of the work in “Before the Clean-Up,” a portal to an earlier version of New York installed in a windowless East Village basement, illuminated only by a ring of LEDs that periodically go dark.

It’s an appropriate, even devotional choice for a show about the nightclub scene of the 1990s, an antediluvian period of make-do spaces where club kids would converge to throw shapes and lose themselves. You see them as they would have been seen, dimly, slipping in and out of euphoric reverie.

It would effectively end in 1997 with Mayor Rudolph Giuliani’s resurrection of the Prohibition-era cabaret law that banned dancing in a club without a license. The party came to a halt, and with it a culture of utopian openness that this show both mourns and memorializes.

In the early ’90s, Nick Waplington was documenting the goings-on in the fashion designer Isaac Mizrahi’s atelier by day. At night he went clubbing at places like Save the Robots, Sound Factory and Limelight, and took visceral and intimate photos, somewhere between party candids and gonzo immersion. His images have almost no critical distance; they appear like family portraits, clammy and tender, ecstasy-dilated pupils and all.

The being-there aura is augmented by Lizzi Bougatsos, an artist-musician and downtown fixture, whose affecting assemblages of clothing and found fragments are like skeletal altarpieces that summon their wearers as if by séance.

One reconstitutes Colin de Land, an influential art dealer who ran the galleries American Fine Art and Vox Populi. In the ’80s and ’90s those galleries cultivated a bohemian, anti-commercial kind of art, a spirit that Smilers seems keen to be haunted by, and from which we’d all benefit. MAX LAKIN

Last Chance

Chinatown

Adriana Ramic

Through March 22. David Peter Francis, 35 East Broadway, Third Floor, Manhattan; 646-669-7064, davidpeterfrancis.com.

It would not be out of place to view Adriana Ramic’s show while crawling, since most of the pieces hang a few inches above the floor. These are six long, thin wooden beams that Ramic adorned with numbered stickers that come with a popular Croatian chocolate bar, each depicting a different animal. (A toucan is 165, a frog, 100.) One has the sense of a child building a collection, trying to understand the world. Blank stretches await new acquisitions.

The main event is right on the floor, a video projected on slabs of dark glass: close-up footage of leaf beetles atop white ginger lilies. Luscious and mundane, the video becomes surprisingly dramatic as these little creatures navigate their minute perches. Will they hold on? Will they eat the smaller insects around them?

Ramic tinted the gallery’s windows so that they suggest the glass holding the beetles. Perhaps we are not so different from these bugs, trapped within their frames? There is a fruitful tension here between scientific, deadpan modes of viewing and attendant emotional effects. ANDREW RUSSETH

More to See

Upper East Side

‘(Re)Generations’

Through Aug. 10. Asia Society, 725 Park Avenue, Manhattan; 212-288-6400, asiasociety.org.

It can sometimes be too easy to see ancient artworks merely as historical relics. Read too much about what the peacock symbolizes in an Indian book illustration, or how Korean ceramics were made, and you may start to feel there’s something illegitimate about your own present-day reactions to their simple colors and forms.

That’s not how the artists Rina Banerjee, Byron Kim or Howardena Pindell want you to feel. In “(Re)Generations,” the three have chosen some exceptionally beautiful pieces from the Asia Society’s Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection to show alongside work of their own, and the result is a persuasive lesson in how to keep art vital even when it’s from long ago and far away.

From Banerjee, who was born in Kolkata and grew up in the world capital of everyday syncretism — that is, Queens, N.Y. — come Buddha heads, a rare seventh-century Haniwa figure from Japan and several dramatic assemblages that incorporate wedding saris, soaring epoxy buffalo horns and the steel trumpet from a 19th-century gramophone. And several memorable collages from Pindell’s “Autobiography” series use picture postcards to recapture, in vivid, almost vibrating detail, memories of her formative travels in India and Japan. In one, Lakshmi, goddess of good fortune, emerges from a colorful ring of mosques and hotels.

But it may be Kim, son of Korean immigrants, who has made the most striking synthesis of old and new by painting a large monochrome especially for this show, titled and modeled after one of several gorgeous pieces of celadon he chose for display. On canvas, in New York, it’s a post-1960s artistic gesture; in Korea, appreciation for the ethereal beauty of monochrome goes back centuries. WILL HEINRICH

Upper East Side

‘Three Perfections’

Through Sept. 28. The Met Fifth Avenue, 1000 Fifth Avenue, Manhattan; 212-535-7710, metmuseum.org.

The real star of the Met’s Asia wing right now is the world’s oldest extant writing system — Chinese characters.

The display starts in the Great Hall, where the Taiwanese calligrapher Tong Yang-Tze’s oversize, thrillingly eclectic treatment of two ancient Chinese poems shows off those characters in all their formal extravagance and historical depth.

“Recasting the Past: The Art of Chinese Bronzes, 1100-1900,” a major exhibition that includes many international loans, is chiefly concerned with the way that ancient ritual vessels and their distinctive shapes have reverberated through Chinese history. But it also includes treasures like a 19th-century ink rubbing of a 12th-century imperial stele inscribed in Emperor Huizong’s own hand, an elegant, self-assured style known as “slender gold.”

Japan has always made inventive use of the writing it adopted from the continent, and the gorgeous screens and ink paintings of “The Three Perfections: Japanese Poetry, Calligraphy, and Painting From the Mary and Cheney Cowles Collection” abound with unforgettable examples. Ryokan Taigu’s 19th-century rendition of the phrase “hundred spring flowers,” a fragment of a famous Zen koan, is loopy and fantastical, while the cheerful aphorisms of Yinyuan Longqi, or Ingen Ryuki, who carried the Obaku school of Zen across the Sea of Japan, look as if they were written last week, instead of the 17th century. And the alternating thick, black strokes and gray, spindly lines of three poems by the monk Tonna, on a kind of 14th-century scratch pad, evoke the soothing, irregular pitter-patter of a summer rain. WILL HEINRICH

Tribeca

‘Light and Abundance: Gold in Japanese Art’

Through April 17. Ippodo Gallery, 35 North Moore Street, Manhattan. 212-967-4899; ippodogallery.com.

The inaugural exhibition at Ippodo Gallery’s new TriBeCa location is devoted to gold in its many craft and aesthetic possibilities. Tea bowls by Noriyuki Furutani have golden “oil spot” glazes dripping down their sides like chocolate; an eight-sided black bronze vase by Koji Hatakeyama has a secretly gilded interior; and hand-hammered brass ginkgo leaves by Shota Suzuki are coated in powdered gold.

Of the many wooden boxes and containers that Jihei Murase has painted with urushi lacquer and covered in still more of this most beautiful of precious commodities, his “Gold Melon-Shaped Water Jar,” with its pockmarked texture and homey bulges, is a particular delight. Only a reflective black lid, tucked away on top, is there to remind you just how glamorous an object it really is.

For my money, though, the most impressive metal in the show is copper, as it appears in a pair of hand-forged vases by Hirotomi Maeda. Called “Clouded Skyscraper” and “Skyscraper Gale,” they’re flat ovals that descend from broad, flat shoulders to narrow feet.

On the first, a pattern of primordial, bright-green spirals stands out against a slate-colored background that somehow looks both slippery and matte; the second is wrapped in wide turquoise lines. In each, the gold around the vase’s neck is completely shown up, turning a yellowish-beige color that evokes millet porridge. WILL HEINRICH

Chelsea

Léon Spilliaert

Through April 12. David Zwirner, 537 West 20th Street, Manhattan; 212-517-8677, davidzwirner.com.

In the most unforgettable picture in this thrilling show, the Belgian artist Léon Spilliaert stands in a dimly lit room and stares straight at — or through — you. It is difficult to be certain because his eyes are shrouded in darkness, just washes of black. In a neat suit, with hair aglow, he is unworldly. It was 1908, he was 27, largely self-taught and ambitious, an illustrator now creating symbolically charged works on paper with ink, watercolor, pastel and the like.

Spilliaert lived in the seaside city of Ostend, where the painter James Ensor (1860-1949) spent most of his life. If Ensor was a master of manic anxiety (menacing clowns, mad skeletons), his younger peer was a specialist in brooding. His coastlines bend and recede until they disappear in lonesome, twilit beach scenes. In one, water laps at the feet of two girls, who are really just black silhouettes, far removed from the faint hotel in the distance.

The exhibition, curated by Noémie Goldman, of the Agnews gallery in Brussels, charts Spilliaert’s range with about two dozen works from the 1900s and ’10s. A brightly lit scene of a woman doing needlework harbors an array of virtuosic marks, while a large bottle is shadowy, unknowable. (A portrait of his perfumer father?)

Spilliaert’s world can feel at once Romantic, overwrought, gothic, proto-surreal and yet true to life. Doom is barely held in abeyance, sometimes not at all. Four bodies are strung up in a tree in a piece inspired by François Villon’s 15th-century “Ballad of the Hanged Men.” A putrid yellow sun is shining, and the tree’s roots are spreading in every direction. ANDREW RUSSETH

Lower East Side

Ho Tam

Through April 6. Carriage Trade, 277 Grand Street, Second Floor, Manhattan; 718-483-0815, carriagetrade.org.

Time for a haircut? Ho Tam has you covered. In 2015, Tam, who was born in Hong Kong and lives in Vancouver, published a photo book on the barbershops and hair salons of Manhattan’s Chinatown, titled “Haircut 100” (though he counted more). His lucid black-and-white images recall Eugène Atget’s desolate photos of early-20th-century Paris, but his focus is people relaxing, laboring and socializing — caring for one another. Spreads from the volume are displayed as mural, including texts he wrote from his research.

One remarkable establishment he visited, which also sold fish balls, is sadly gone from Henry Street, a gallery row these days. Tam’s project is a tribute to Chinatowns and so-called third places — social venues apart from home or work — which are increasingly scarce, and expensive, in some areas. I recently paid $12 for a slice of cake downtown, the price of a cut at some of these establishments. ANDREW RUSSETH

Closed

Tribeca

Betty Parsons

Through March 15. Alexander Gray Associates, 384 Broadway, Manhattan; 212-399-2636, alexandergray.com.

As an artist, Betty Parsons (1900-82) has long been underrated. She is in the history books as a venturesome New York art dealer, championing Abstract Expressionists, a role that overshadowed her art practice. This taut show of nine paintings from the 1960s reveals another obstacle Parsons has faced: She was a restless talent, never settling into a major, signature style, like Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock or her other luminaries. That makes her hard to market, but easy to identify with, and to admire.

Some of the pictures here are astonishing. “Reverberation” (1968) is a vertical wonder, nine feet tall, of loose, hesitant organic forms, with strange repetitions, asymmetries and hints of the body. A jazzy, amoeba-like small gouache, “Palm Beach Xmas” (1960) has Elizabeth Murray’s exuberance, while “Without Greed” (1960) is a deep burgundy field holding peculiar forms. The best work may be the rough-hewed “Sand With Shapes” (1966), populated by spectral beings or architecture.

“I’m always changing,” Parsons said the year before she died, referring to her art. “I never know what I’ll say or do next.” Her works exude a profound commitment to intuition. At a time when many artists (and dealers) chase trends, it would be nice to see a Parsons survey — including the charming painted driftwood pieces she made later in life — in a blowout retrospective, ideally at a museum in her hometown. ANDREW RUSSETH

See the February gallery shows here.