At Stockwell Tube station in south London, Metropolitan Police firearms officers were congratulating themselves on a job well done. They believed they’d just shot dead a failed al-Qaeda suicide bomber, Hussain Osman.

His body lay slumped in a seat on a stationary Northern Line train at platform two, his denim jeans and jacket covered in blood. Fearing that he was carrying a device, the officers withdrew to the central hub of the Underground station and called in an explosives officer to check and make the scene safe.

It was just after 10am on a Friday morning towards the end of July 2005, a month in which 52 Londoners had died and hundreds had been injured in a wave of vicious al-Qaeda suicide bombings targeting transport links.

A second wave had just been foiled, the bombs at three Underground stations and on a bus fizzling out and the perpetrators making their escape. The capital was on high alert, fearing more attacks. But at least one suspect was down, tracked and shot by armed police officers.

Or was he? Explosives expert Ian Jones arrived at the eerily deserted station, raced down the escalator, boarded the train and saw the dead man slumped over a seat with his bloodied head resting low against a vertical handrail. He checked for a body belt or any sort of device beneath his clothing but detected nothing. In the man’s pockets he found a wallet and a mobile phone but nothing else.

He was puzzled. Everyone he’d spoken to seemed so certain this man was a bomber. That’s what ‘Charlie 2’ and ‘Charlie 12’, the two police firearms officers who’d pulled the trigger, had told him.

As a precaution, he X-rayed the dead man’s mobile phone and shoes. Again, nothing. He recalls: ‘I knew then that it was absolutely disastrous, for him and his family but also for the Met. They had tried really hard to stop another terrorist incident and it had gone wrong.’

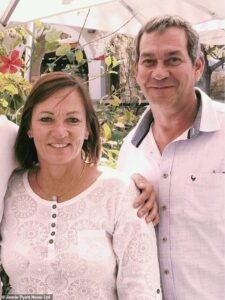

Jean Charles de Menezes was shot after he was suspected of being a terrorist after the 7/7 bombings

The police had been searching for suspect Hussain Osman, pictured

On the station forecourt, the media had arrived and were interviewing witnesses. ‘I saw an Asian guy run on to the train,’ said one. ‘He had a baseball cap on, and a thickish coat. He might have had something concealed under there, I don’t know.’

He described a plainclothes police officer holding a black automatic pistol in his left hand and unloading five shots into the man. ‘It was no less than five yards away from where I was sitting. He looked absolutely petrified, like a cornered rabbit.’

Other witnesses described the subject as Asian, claiming he’d jumped over the ticket barrier and appeared to have a bomb belt and wires hanging from him. Soon on the scene was Detective Superintendent John Levett, head of specialist investigations for the Met’s Directorate of Professional Standards (DPS), its anti-corruption unit.

He could instantly see the perils of the situation. ‘We, the British police, had shot dead a person without any warning in public, using a tactic [shoot to kill] never used on the mainland before. It was a watershed moment in policing.’

Levett’s job was to carry out an initial investigation but then hand over the job of establishing the truth about what had happened to the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC), a body established just a year earlier and not part of the police force. But while on his way to Stockwell, Levett received a phone call that the IPCC was to be excluded from the scene.

He felt uneasy with the instruction, wondering if it was even legal, and he questioned it. ‘I was told that it had come from the highest authority, from Mr Blair. I said, “The Commissioner doesn’t have that authority.” I was told it wasn’t Sir Ian Blair, the police Commissioner. It was the Prime Minister, Tony Blair, and that there had been a meeting between the Commissioner and the PM to say that, in the event of a terrorist incident, the IPCC was to be excluded from the scene.’

There were four people in the car. Levett says: ‘I made sure that everyone had heard what was said and that I’d questioned the decision. I made sure it was written down.’

Ian Blair defends his decision to bar the IPCC. ‘This was probably the most desperate afternoon that we ever had,’ he says. ‘I didn’t want anything getting in the way of that.’ He also denies that the Prime Minister was involved in the decision; for his part, Tony Blair has no recollection of having such a conversation with the Met Commissioner.

But when news of the IPCC’s exclusion reached senior officers at New Scotland Yard, they were alarmed. Assistant Commissioner Andy Hayman, in overall charge of counter-terrorism, thought the decision ‘just bizarre’. ‘If you shut the door in the IPCC’s face,’ he says, ‘people are going to smell a rat, that something isn’t quite right.’

Acting Assistant Commissioner Brian Paddick protested: ‘That’s the most stupid decision I’ve ever heard.’ Home Secretary Charles Clarke tried to have the decision reversed, but to no avail. He thought ‘a wrong-headed defensiveness’ was behind the decision.

On arrival at Stockwell station, Levett requested the CCTV from the Tube train and the platform, hoping to see the shooting first-hand. He was told that neither existed. The only CCTV available was from the ticket hall. ‘Why was the other CCTV missing?’ Levett wondered. ‘I worried that people would start to think there was a conspiracy.’

He recalls that senior officers were constantly ringing him, demanding to know who the individual was who’d been shot. He rebuffed the pressure. And to protect his credibility, he insisted he would only go down to the carriage if accompanied by a video team and a coroner – the video team so he couldn’t later be accused of tampering with the evidence, the coroner as an irreproachable witness.

Several hours passed before Levett and his team descended the steps and walked along platform two to the carriage where a man lay face down. ‘It was carnage,’ he recalls. ‘He’d been shot in the head.’ Levett had been given a photograph of Osman, but the damage to his face made identification impossible.

Former Metropolitan commissioner Sir Ian Blair

De Menezes’s aunt, Maria Aparecida comforts his mother, Maria Otone, next to his father, Matuzinho

‘His wallet was on the seat of the Tube train, however. Inside, there was ID to suggest that it belonged to a Jean Charles de Menezes, who was born in Sao Paulo in Brazil.’

There were already rumours racing around that the dead man might not in fact be the suspect, Hussain Osman, beginning with detectives on the scene who had checked the mobile phone found on the body for recent calls and contact numbers in the hope of finding details of the other suicide bombers.

But the messages were all in Portuguese, not a language or people associated with al-Qaeda or terrorism of any sort.

Senior Investigating Officer Doug McKenna got a sinking feeling after a call from the scene saying: ‘I’m not convinced that it’s Hussain Osman.’

An hour after the shooting, forensic investigator Steve Keogh received word that ‘it looks like the wrong person’. At Scotland Yard, Assistant Commissioner Andy Hayman was shocked and ‘very concerned’ when it became clear that the body in the carriage was not Osman. But there was no clarity as to what had actually happened. ‘Was this another terrorist?’ he wondered. ‘An associate of Osman? Did the dead man steal that ID? He’d been shot in the head so visual identification wasn’t possible.’

That afternoon, Ian Blair and Andy Hayman held a press conference, the purpose of which, they agreed, was just to release images of four suspected bombers who’d been caught on CCTV the day before.

Whatever had happened at Stockwell, there were still potential suicide bombers out there who had to be found and stopped.

Hayman was therefore startled when Ian Blair announced that ‘as part of the operations linked to yesterday’s incidents, Metropolitan Police officers have shot a man inside Stockwell Underground station and the man was pronounced dead at the scene’.

He went on: ‘My information is that this shooting is directly linked to the ongoing and expanding anti-terrorist operation. As I understand the situation, the man was challenged and refused to obey police instructions.’ (Ian would later claim that at this point he’d been told nothing about the Brazilian identity documents found on the dead man or the fact that his phone messages were in Portuguese.)

As he listened to the commissioner, Hayman shuffled uncomfortably. For those like him who’d heard directly from the scene at Stockwell that firearms officers had shot ‘the wrong man’, Blair’s claims made no sense.

He reflects now: ‘It was a big shock to hear him start talking about the shooting, inferring that we’d shot someone who was a terrorist. As far as I was concerned, that information was not known.’

The media understandably seized on the shooting. Rolling news reported eyewitness descriptions of the dead man appearing to be ‘Asian’, running away from police officers, jumping over the ticket barrier and, on a warm July morning, wearing a thick coat.

Off the record, Hayman tried to put the record straight, telling crime reporters that the man shot dead at Stockwell was not one of the four suspects from the failed attacks a day earlier. Finally, BBC News 24 reported: ‘The man shot dead at the Tube station is not thought to be one of the four men shown in CCTV pictures released this afternoon.’

Meanwhile, at Stockwell Tube station John Levett received word that the Anti-Terrorist Branch had no further interest in De Menezes. All day, he had been expecting someone senior to turn up and assess the scene for themselves but no one did. Yet here was the decision being formally made that the man they’d killed was a completely innocent man, a victim of a police shooting.

Levett wrote a press release which he deliberately kept bland. It read: ‘During a counter-terrorism operation at Stockwell Tube station, a 27-year-old Brazilian man was unfortunately shot dead. Our condolences go to the family.’ He submitted it to his superiors before going to bed.

Armed police outside Stockwell Tube station after De Menezes was shot

But when he woke the next morning and switched on the TV news, he was surprised that the bulletins were still repeating claims that the unnamed man shot dead at Stockwell had leapt over the ticket barriers and run from police while wearing an unseasonably heavy jacket.

The rolling news channels wheeled in former senior officers and security specialists to comment, all of whom agreed that a combination of intelligence and the dead man’s behaviour and dress must have left officers with no choice but to gun him down. But Levett had examined the body. He knew that De Menezes was wearing a light denim jacket, not a thick coat.

When he got to his office, he called for the CCTV footage from the foyer and escalators at Stockwell station. They alone discredited the news reports. ‘You see him walking into the ticket hall,’ says Levett. ‘He grabs a newspaper, puts it under his arm, uses his Oyster card to go through the barrier and then goes down the escalator. At no point is he running.’

What Levett saw on the CCTV contradicted the press release issued by the Met, which stated that ‘his clothing and his behaviour added to suspicions’.

Ian Blair seemed to be one of the only people at Scotland Yard ignorant of the fact that the force had shot an innocent man

Levett contends that senior officers hadn’t checked their facts with him, or with officers involved in the shooting. He demanded a meeting with Deputy Assistant Commissioner John Yates, during which he spelled out the inaccuracies. But it seemed the damage had already been done. To this day, many people still believe that De Menezes had been wearing a bulky jacket, jumped the ticket barriers and ran from the police before he was shot dead, none of which is true.

That Saturday morning, Ian Blair seemed to be one of the only people at Scotland Yard ignorant of the fact that the force had shot an innocent man.

When confronted by journalists as he arrived for work, he declared that ‘the Metropolitan Police is playing out of its socks. It’s a fantastic investigation and a fantastic response.’

Blair says now: ‘I said what I said because that’s what I believed. At that point I didn’t know anything more than I did the night before. And then, once I walked into the Yard, within five minutes, I realised that we’d got a disaster on our hands. And it was a shock, a very bad shock for everybody.’

Soon after, police released a statement saying they were ‘now satisfied’ that the unnamed dead man had nothing to do with the failed bombings on July 21, although they reiterated their opinion that his ‘clothing and behaviour’ had caused suspicion. That evening they revealed the identity of the man they’d shot almost 36 hours earlier.

The following day, Ian Blair admitted his officers had made a mistake, telling Sky TV’s Sunday show: ‘This is a tragedy. The Metropolitan Police accepts full responsibility for this. To the family, I can only express my deep regrets.’

By now, the media had tracked down Patricia and Vivienne, cousins and flatmates of De Menezes in Tulse Hill, south London. They revealed that he been very happy living there. Indeed, one of the things he liked most about the city was that the police weren’t armed and were always courteous.

Assistant Commissioner Andy Hayman was shocked and ‘very concerned’ when it became clear that the body in the carriage was not Osman

Police and London Underground workers at the entrance of the Tube station

In the days that followed the shooting, a makeshift memorial to him sprouted outside Stockwell station, a gathering point for campaigners seeking answers about the incident. One of their questions was why, in the days after the shooting, Ian Blair and the Met Police continued to denigrate his reputation by implying that he’d behaved suspiciously.

His family were angry, making clear their determination to see those culpable for this ‘cold-blooded murder’ brought to justice. Top of their list, the Metropolitan Police Commissioner. ‘He’s the person who’s most responsible for what’s happened,’ said Patricia. ‘It was a series of errors which began at the top and then ended up with an officer killing my cousin. I think all of them should be prosecuted.’

Ian Blair – who was ennobled in 2010 – is now 72 and long retired. He holds his hands up to a series of misjudgments around the shooting, beginning when Hayman told him that someone had been shot at Stockwell Tube station.

‘Because the Met had never, to my knowledge, shot an innocent man or woman in a pre-planned operation, I just assumed that we’d shot a bomber. And a lot of the things that went wrong thereafter came from that early misunderstanding.’

His next admission is why he’d said, ‘this shooting is directly linked to the ongoing and expanding anti-terrorist operation’ during the press conference. ‘I wasn’t told he was a Brazilian. And then the press office drafted me a statement which ends with the words, “he was challenged and refused to obey”.

‘But you don’t challenge a suicide bomber. You don’t give them the chance. You shoot them. But now it sounded as though I was deliberately telling a lie about what had happened. I wasn’t, but I should have seen the significance of that line.’

Brian Paddick, Ian Blair’s Acting Assistant Commissioner on the day, feels that the Met could have taken measures to remedy this mistake. ‘The problem is that the Met didn’t retract what Blair said.

‘Unfortunately, in the past the Metropolitan Police have had a policy of trying to besmirch the character of people they shoot, so there was the usual police campaign to try to undermine the character of the person to make it look slightly less of a problem. It was disgraceful.’

Ian Blair concedes: ‘I was head of that organisation, I’m accountable for that death. I’m quite clear that I could have done better. But it’s difficult to recreate the atmosphere at the time. It was frantic, and neither I nor anyone else was thinking terribly straight. We just knew we had to do everything we could to find those people.’

Three days after being barred from attending the scene of the shooting, the IPCC took over the official investigation, as it was required to do by law. As they trawled through every piece of paperwork, senior investigators John Cummins and Steve Reynolds were troubled by some of the police culture and behaviour.

After the shooting, the firearms officers had returned to their base, handed in their weapons and ammunition, and were immediately given legal advice not to provide any account of the shooting at that moment, but reconvene the following day to make their detailed written statements.

Then, when making these statements, they were allowed to write their notes together and confer, which Reynolds believes was wrong. ‘Why are police officers who have shot somebody dead treated differently to any other suspect?’

Then there was the interviewing of the 17 civilian witnesses of the shooting. Most had fled through a short tunnel to a neighbouring Victoria Line platform, then jumped on a northbound train. Alighting two stops later at Pimlico, they went to a pub, from where they called the police.

Uniformed officers arrived and interviewed them there, despite the TV being on in the background and reporting live from the scene. And yet many of the witnesses interviewed on TV that day were saying things that later turned out to be untrue. In addition, a police officer was heard to say to witnesses: ‘You shouldn’t be saying things like that, an officer could lose his job.’

As Cummins and Reynolds continued their investigation, they discovered that there appeared to be a concerted campaign to damage the reputation of the victim. Even after it was known that De Menezes wasn’t a terrorist, official police press releases described him as wearing suspicious clothing and acting unusually.

Several newspapers also quoted a Home Office claim that his UK visa had expired and that, at the time of his death, he’d been carrying a forgery. The implication was clear – this must have been why he ran from the police. In fact, not only had he not run, evidence would later emerge that he was fully entitled to be in the country at the time of his death.

The IPCC discovered that the police gunmen in the carriage claimed they’d shouted warnings of ‘armed police!’ several times, and that De Menezes stood up and walked towards them. However, not a single civilian witness from the carriage recalls hearing a warning.

Witnesses also insist that he never got out of his seat. They remarked on how calm he remained, even as a gun was being held to his head, as if he were waiting for instructions. Later, the IPCC report suggested that these officers be referred to the Crown Prosecution Service on the basis that they ‘conspired to pervert the course of justice’. But no further action was taken.

Almost a year after the killing, the Crown Prosecution Service announced that no police officers would be prosecuted over De Menezes’s death. But under health and safety laws, a criminal prosecution was brought against Commissioner Blair as head of the Met for failing to protect members of the public. The Met pleaded not guilty, taking it to trial.

De Menezes’s parents and a family friend leave the Tube station, where flowers and letters had been left

According to senior sources, the ‘not guilty’ plea had been at Blair’s insistence. ‘He was advised to plead guilty, take the beating and move on. But he insisted we must plead not guilty in the face of opposition from all around him.’

At the trial, the Met’s defence team mounted a brutal character assassination of the dead man, suggesting that he might have been high on cocaine and therefore jumpy and paranoid, that he had acted like a suicide bomber, and had been aggressive and threatening.

The Met released a composite picture intending to show how alike De Menezes was to Hussain Osman. It emerged that the picture had been distorted, stretched or resized, creating a misleading match.

The force was found guilty of endangering the public and fined £175,000, with £385,000 costs. The judge criticised its ‘entrenched position’ in refusing to admit any failures in the operation.

Yet at the subsequent inquest into De Menezes’s death, the Met still claimed that its officers had lawfully killed him as part of a counter-terrorism operation and that he had moved towards them in a menacing fashion before they opened fire.

Officer C12 even claimed he shouted ‘armed police’. But the jury unanimously decided there was no warning and that De Menezes did not move before he was grabbed, then shot at point-blank range.

However, the coroner prevented the jury from returning a verdict of unlawful killing by police, provoking accusations from several quarters that the inquest was a whitewash. They decided on an open verdict, the most critical available to them.

In 2009, the Met Police settled a damages claim with the family of De Menezes. The amount of compensation paid was not revealed.

Adapted from Three Weeks In July by Adam Wishart and James Nally (Mudlark, £25), to be published on June 19. © Adam Wishart and James Nally 2025. To order a copy for £22.50 (offer valid until June 21, 2025; UK P&P free on orders over £25) go to mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937.