On a normal day, the Guadalupe River runs lazily through the scenic hills of Kerr County, Texas – past campsites where families sunbathe on its banks, fish for trout, or float gently downstream.

But in the early hours of July 4, after a torrential downpour, a black wall of water swept down the valley, tearing through everything in its path and leaving more than 100 people – including at least 27 camp counselors and children – dead. As rescuers and emergency services comb the destruction for bodies days later and families try to find their loved ones and salvage their homes – it seems at first glance like the floods were the worst kind of freak natural tragedy.

But now, experts have told the Daily Mail it was anything but a ‘freak’ event – in fact, they say the very features which make the river so scenic on a good day, made the disaster almost inevitable. ‘They call this area of Texas flash flood alley,’ Nicholas Pinter, a professor of Applied Geosciences at UC Davis, told the Daily Mail, ‘I can’t think of a place more susceptible to flash flooding in the country.’

Pinter said the floods happened thanks to a ‘cursed’ combination of ‘meteorology, topography and geology’ in the area.

First came the torrential rain, pushed inland from the Gulf of Mexico.

‘When these types of events happen you get a lot of moisture coming inland from the Gulf, it rises as it moves across Texas and then you get a lot of rain,’ Professor of Atmospheric Sciences at Texas A&M, Andrew Dessler told the Daily Mail.

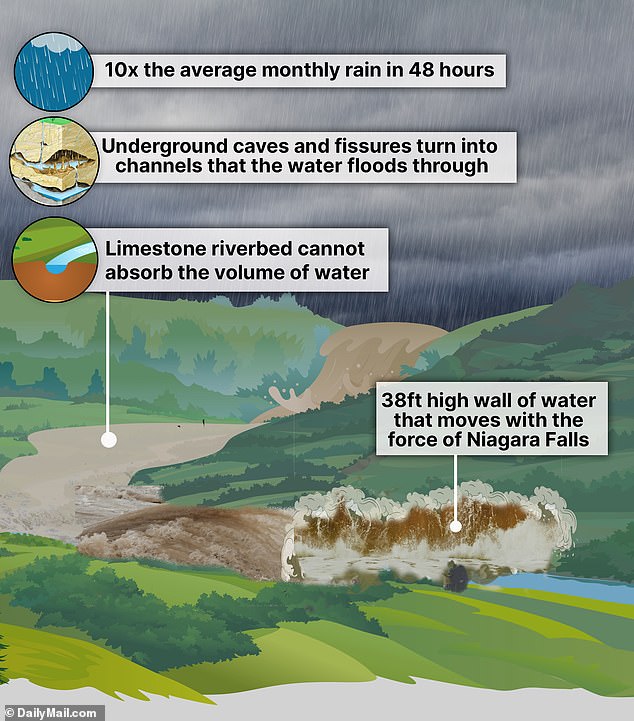

Over ten times the average monthly rainfall fell in the area over the weekend with some places seeing 20 inches in just a few hours on July 4.

Then, the hills and valleys which make the area so beautiful meant that all that rainwater was funneled into one place.

The devastating floods happened thanks to a ‘cursed’ combination of ‘meteorology, topography and geology’ in the area surrounding the Guadalupe River.

‘If Houston got 12 inches of rain, it would have literally no effect, it’s very flat so it would all spread out and they have very good infrastructure for handling it,’ Dessler said.

‘But if you dump water over hills, like in this area, the water runs down the hills into these low valleys and then gets concentrated there, and runs into the rivers and the rivers rise rapidly,’ he added.

To make matters worse, the area’s geology means that the water flowed particularly quickly. There is only a thin layer of soil on top of a bedrock layer of limestone and it can’t absorb very much water.

Pinter explained, ‘Limestone creates fissures and caves underground which the rainwater funnels into. It essentially creates big pipes of water which then run out straight into the rivers at a very fast pace.’

A drought in the weeks before meant the ground was even harder and less absorbent than it might otherwise have been, meaning water could run straight off it into the rivers.

‘It’s the worst case scenario there of any place,’ Pinter said.

The combination of the rainfall, steep hills and geology meant the Guadalupe river overflowed within seconds.

‘It rose more than a full story of water within 15 minutes,’ Pinter said, ‘It was lethal and terrifying.’

The floodwater crested at a record breaking 37.5 feet – a horrifying wall of water that, at its peak, moved with a force greater than the average flowrate across Niagara Falls.

Within ten hours the river’s pace had surged from 10 cubic feet per second to 120,000.

Despite weather forecasts predicting the rain and issuing flood warnings, this happened so quickly in the middle of the night that those sleeping on the banks of the river had no time to escape.

‘If you look, about eight hours before they forecast there was going to be a lot of rain and flooding, and then three hours before they said the Guadalupe was rising rapidly and that people should take action,’ Dessler said.

‘But it was the middle of the night,’ he added, ‘and the warnings from the weather service didn’t get to the people in harm’s way. That’s where the breakdown was.’

Over ten times the average monthly rainfall fell in the area over the weekend with some places seeing 20 inches in just a few hours on July 4.

Within ten hours the river’s pace had surged from 10 cubic feet per second to 120,000.

The floodwater crested at a record breaking 37.5 feet – a horrifying wall of water that, at its peak, moved with a force greater than the average flowrate across Niagara Falls.

Despite weather forecasts predicting the rain and issuing flood warnings, this happened so quickly in the middle of the night that many simply had no time to escape.

Dessler warns that with climate change, flash floods like this are going to grow more and more common.

‘Climate Change is juicing these storms,’ he said, explaining that warmer weather means there is more water in the air and more heavy rain, ‘it’s loading the dice to give us more of these events.’

‘We have to be prepared for these kinds of events to happen more frequently, because they are going to happen more frequently,’ he added.

For those living in at–risk areas, like Kerr County, Dessler recommends planning ahead.

‘They need to have a weather radar, and they have to have a plan for what happens if the weather service says they’re going to have a lot of rain upstream,’ he said.

‘For things you can’t get out of harm’s way, you need to build infrastructure – if you have a hospital you have to build flood infrastructure around it, and all these things are very expensive,’ he added.

‘The choice is, we can head off this unlikely but really terrible event, but we’ll have to pay for it – and often people don’t want to do that – and then they roll the dice, and something like this happens,’ he said.

But, as this weekend’s tragedy proves, in flash flood alley, the costs are worth it.

Dessler said: ‘These events do happen and they do kill people.’